Providing stable freshwater supplies is a priority for every country in the world. Yet stable supplies are increasingly hard to come by in many countries, as water-related risks increase. For example, recent droughts threatened GDP growth in the United States. Monsoon floods killed hundreds and displaced thousands in India. Increased competition for water may impact energy production in China, and the list goes on.

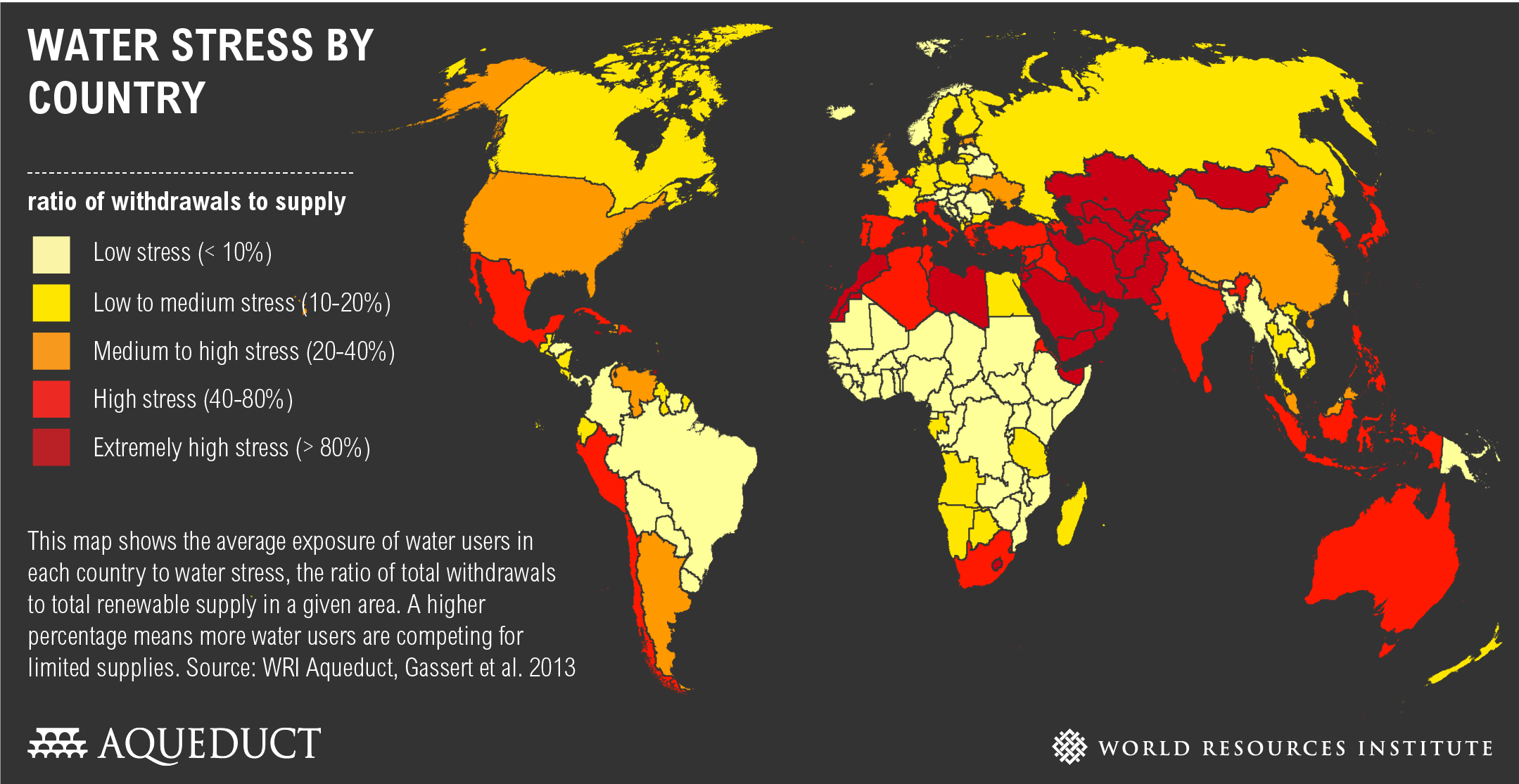

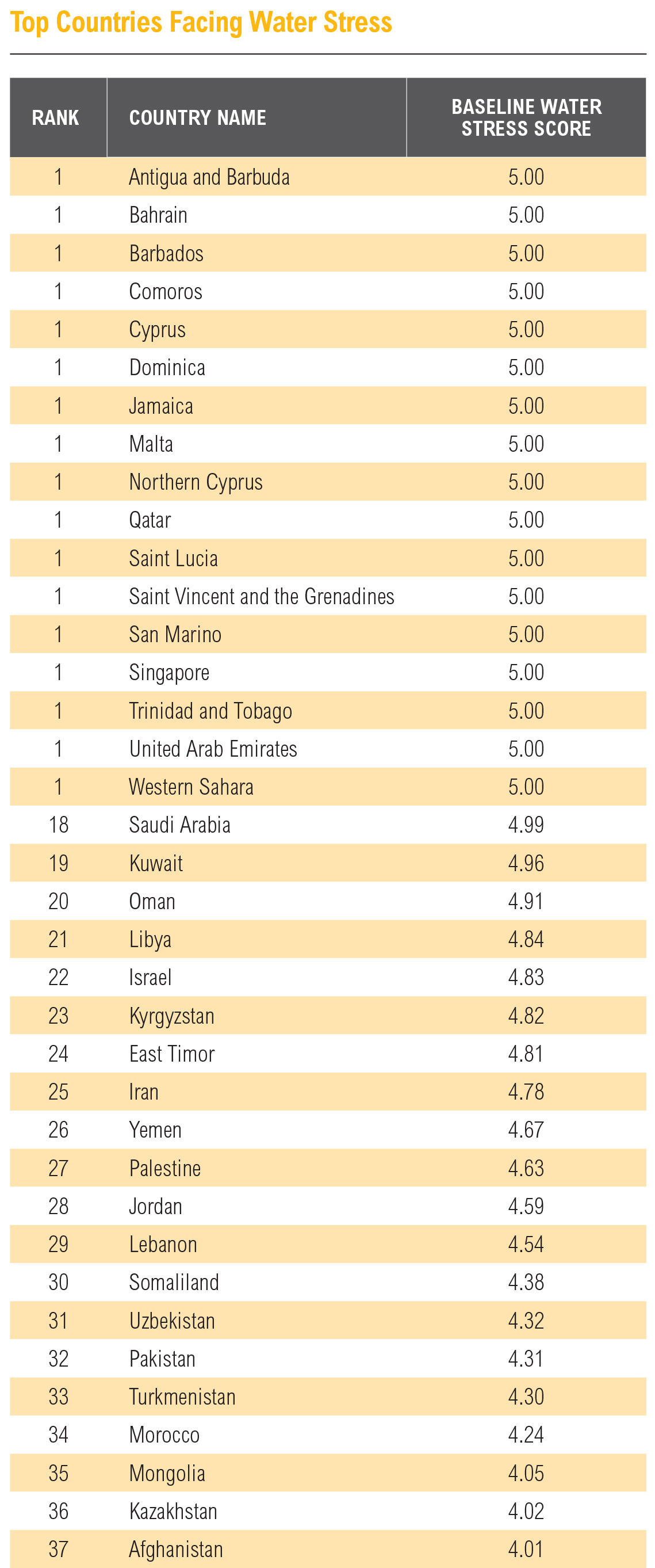

WRI’s Aqueduct project recently evaluated, mapped, and scored water risks like these in 100 river basins, ranked by area and population, and 181 nations—the first such country-level water assessment of its kind. We found that 37 countries face “extremely high” levels of baseline water stress (see list at bottom). This means that more than 80 percent of the water available to agricultural, domestic, and industrial users is withdrawn annually—leaving businesses, farms, and communities vulnerable to scarcity.

Evaluating National Water Risks

We started with local-level data from the Aqueduct Water Risk Atlas. Using statistical methods to account for where water is being used within a particular country, we brought this local-level data to the country scale, looking at baseline water stress, as well as floods, droughts, inter-annual variability, and seasonal variability. Countries received a score of 0-5 for each indicator—the higher the score, the greater the exposure to that particular water risk.

Baseline water stress measures how much water is withdrawn every year from rivers, streams, and shallow aquifers for domestic, agricultural, and industrial uses. Scores above 4 indicate that, for the average water user, more than 80 percent of the water available is withdrawn annually. That means companies, farms, and residents are highly dependent on limited amounts of water and vulnerable to even the slightest change in supply. Such situations severely threaten national water security and economic growth--especially if a country does not have adequate water-management plans in place. National and local governments must respond with management and conservation practices that will ensure long-term availability of water resources for all users, including the environment.

Why Is It Important to Analyze Water Risk at the Country Level?

Our analysis reveals that 37 percent of countries we assessed experience high to extremely high baseline water stress. This information is highly relevant for a country’s economy, environment, and communities. Yet until now, scant country-level water risk data existed.

Water data is usually collected and reported at local geographic scales. However, water-related decisions and investments are often made at much larger scales, requiring country-level information. Commercial banks, for example, usually evaluate certain types of risk (e.g. political, social, and economic risk) to their global portfolios at the country level. Without accurate measures of countries’ water risk, such banks might ignore water-related risks to their investments. There is, therefore, a compelling need to translate locally collected or locally modeled water risk data to the country level.

A Look at Countries’ Water Risks

Our interactive map and working paper share the average exposure to five of water-quantity risk indicators for all countries and major river basins worldwide. These indicators include:

- Baseline water stress: the ratio of total annual water withdrawals to total available annual renewable supply.

- Inter-annual variability: the variation in water supply between years.

- Seasonal variability: the variation in water supply between months of the year.

- Flood occurrence: the number of floods recorded from 1985 to 2011.

- Drought severity: the average length of droughts times the dryness of the droughts from 1901 to 2008.

Extremely High Water Stress Can Be Managed

It’s also important for countries to understand the underlying natural factors that drive their water-related risks and respond accordingly. Extremely high levels of baseline water stress, for example, don’t necessarily mean that a country will fall victim to scarcity. Armed with the right information, countries facing extremely high stress can implement management and conservation strategies to secure their water supplies.

Singapore, for example, has the highest water stress ranking (5.0). The country is densely populated and has no freshwater lakes or aquifers, and its demand for water far exceeds its naturally occurring supply.

Yet the country is consistently held up as an exceptional water manager. Singapore invests heavily in technology, international agreements, and responsible management, allowing it to meet its freshwater needs. Advanced rainwater capture systems contribute 20 percent of Singapore’s water supply, 40 percent is imported from Malaysia, grey water reuse adds 30 percent, and desalination produces the remaining 10 percent of the supply to meet the country’s total demand. These forward-thinking and innovative management plans provide a stable water supply for Singapore’s industrial, agricultural, and domestic users—even in the face of significant baseline water stress.

Aqueduct’s country rankings and map make it easy to quickly assess country-level water risk, as well as compare exposure to water-related risks between countries. This information will help governments, financial institutions, companies, and research organizations better prioritize high-risk areas for investments in improved water management. In that sense, country-level water risk data is a key tool in moving the world toward a water-secure future.

- LEARN MORE: Check out our interactive water risk map.

- CBCSD and Members Participated and Suggested on the Project for Technical Regulation on Low-carbon Pilot Community

- CBCSD and Members Participated in the APEC Cooperation Network Construction Forum of Green Supply Chain

- Calculation Method of CO2 Emissions in Petroleum and Natural Gas Exploitation Enterprises & Calculation Method of CO2 Emissions in Water Network of Chemical Enterprises

- CBCSD Attended the Workshop for Environmental Protection and Sustainable Development and Delivered Introductions

- WBCSD: Tackling the Challenge, How to Make Informed Choices on Forest Product?

- The National New-Type Urbanization Plan Released, Board Members of CBCSD Help the Sustainable Development of Cities

- Board members of CBCSD Actively Participated in the Carbon Trading and International Climate Change Process

- Two industrial Standards Compiled by CBCSD Passed Examination

- Widespread Use of the Achievements Businesses Energy Saving and Greenhouse Gas Management

- CBCSD held Chemical industry enterprise value chain (range 3) greenhouse gas emissions, accounting and reporting guidelines