China’s hunger for power will mean that China’s water resources will be even more stretched (Image by Hervé BRY)

When we think about water use, we think about the water we drink, but we also need water to grow food, generate electricity, make our clothes and extract minerals. In short, water drives the economy. In China, 97% of electricity generated requires water to produce, so no water literally means no power.

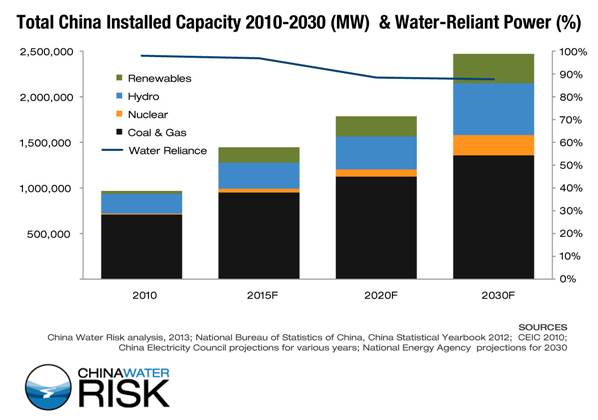

Between 2010-2030, China plans to add 1.2 terawatts of water-reliant power. This is equivalent to adding more power than the combined installed power generation capacity of the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia today. Coal is central to China’s energy policy.

Despite China’s efforts to curb its carbon emissions by cutting reliance on coal from around 70% of its energy mix to 55%, China’s coal-fired capacity is expected to increase by the equivalent of 450 gigawatts. This addition in coal-fired power is more than double the whole of India’s power generation today.

The role of coal in air pollution has received a lot of attention; lesser known is its impact on water. Not only is it water intensive to mine, it is also polluting.

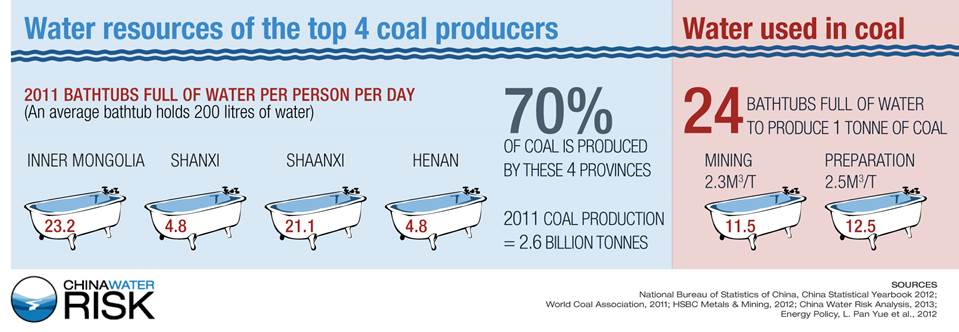

Around 95% of China’s coal is mined underground with heavy reliance on groundwater use. In Shanxi province, studies estimate that 1.07m3 of groundwater is destroyed per tonne of coal extracted. With around 70% of coal production coming from Inner Mongolia, Shanxi, Shaanxi & Hebei provinces, this may lead to further deterioration of the already polluted groundwater in the North China Plain.

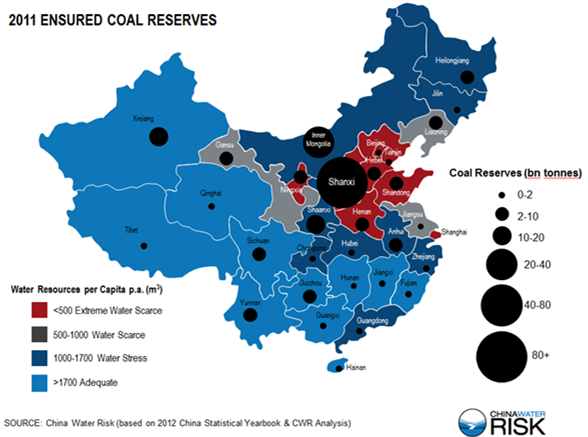

Worse still is that 53% of China’s ensured coal reserves lie in water scarce regions and 30% lie in water stressed regions.

It takes 24 bathtubs full of water to extract and wash one tonne of coal. China’s top coal producing provinces produced 2.6 billion tonnes of coal in 2011, but only have water resources equivalent to 4.8 to 23.2 bathtubs of water per person per day.

Given this, surely it is time to ask if China has enough water to fuel its power expansion plans?

The Ministry of Water Resources has recently moved to address this with the Water-for-Coal Plan released in December 2013 which states that future development of large coal bases in China will depend on the availability of regional water. Miners can invest in technology that not only treats wastewater but allows them to extract more coal with less water.

Indeed the 2011 water-in-mining spend in China is a mere US$230 million compared with US$1.5 billion in Australia and US$794 billlion in Peru. With water-reliant power generation expected to remain high (falling from 97% to 87% by 2030), energy and water policies are expected to continue to dovetail.

Unfortunately alternatives to coal such as gas, nuclear and hydropower, although better for air are also all constrained by water availability and each has its own set of serious implications. There are worries globally on the impact of water aquifers by hydraulic fracking for shale gas.

Recently, 19 Chinese NGOs published a report saying that hydropower stations significantly damage China’s rivers. China’s 20,000 big dams are not only disrupting river flow causing transboundary river basins to fragment but could be changing ecosystems and endangering biodiversity. The planned build-out is significant: hydro capacity is expected to expand from 216 gigawatts in 2010 to 568 gigawatts by 2030.

This is an increase equivalent to Japan’s and Australia’s installed capacity at as of 2009. With this size of hydropower expansion, China’s search for clean energy may bring about geo-political tensions with neighbouring countries as transboundary rivers such as the Upper Mekong, Salween and the Brahmaputra will be dammed.

The focus should not just be on ‘using less water’, but on ‘saving energy’ as using less energy also saves water. The government’s push in the strategic emerging industry of “Environmental Protection & Energy Savings” is expected to do just that. If China does not employ “energy saving” strategies, China’s hunger for power will mean that China’s water resources will be even more stretched.

- CBCSD and Members Participated and Suggested on the Project for Technical Regulation on Low-carbon Pilot Community

- CBCSD and Members Participated in the APEC Cooperation Network Construction Forum of Green Supply Chain

- Calculation Method of CO2 Emissions in Petroleum and Natural Gas Exploitation Enterprises & Calculation Method of CO2 Emissions in Water Network of Chemical Enterprises

- CBCSD Attended the Workshop for Environmental Protection and Sustainable Development and Delivered Introductions

- WBCSD: Tackling the Challenge, How to Make Informed Choices on Forest Product?

- The National New-Type Urbanization Plan Released, Board Members of CBCSD Help the Sustainable Development of Cities

- Board members of CBCSD Actively Participated in the Carbon Trading and International Climate Change Process

- Two industrial Standards Compiled by CBCSD Passed Examination

- Widespread Use of the Achievements Businesses Energy Saving and Greenhouse Gas Management

- CBCSD held Chemical industry enterprise value chain (range 3) greenhouse gas emissions, accounting and reporting guidelines